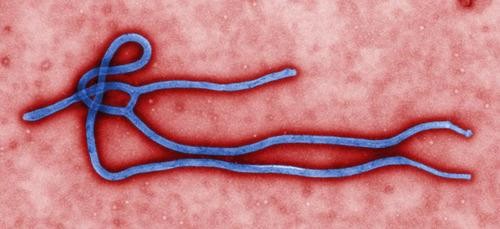

Photo by C.S Maureen

Yahoo News is reporting that two Americans infected with Ebola will be treated in the United States, marking the first time the deadly virus has been treated within U.S. borders.

The evacuations of Dr. Kent

Brantly and missionary Nancy Writebol are being facilitated by the State

Department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emory

University in Atlanta announced at a press conference on Friday that it

will be treating two patients with the Ebola virus.

As of this week, Ebola virus disease (EVD) has killed more than 700 people,

according to the World Health Organization. There is no cure and no

vaccine for EVD, which kills between 60 and 90 percent of its victims.

The current outbreak — the largest in history — originated in Liberia

and has spread to neighboring countries, but it has been contained thus

far to West Africa.

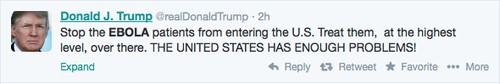

The news that people infected with disease will be treated here in the U.S. sparked quite a reaction on social media, inspiring even a certain celebrity billionaire to take to Twitter in protest:

CDC director Thomas Frieden, M.D., called Ebola “a dreadful, merciless virus” on a press call on

Thursday, so it’s understandable that Americans would be concerned. But

the chance that someone in the general population will contract Ebola

is still extremely small.

"This is a very low-risk

situation for the general U.S. population," Diane Griffin, M.D.,

professor and chair in molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns

Hopkins University, told Yahoo Health. "Emory is a great place for [the

patient] to go. They are set up well to handle this type of situation."

Ebola is not spread like the cold

or the flu, she added. You could be sitting next to someone who is

infected and still not contract the virus. “It’s transmitted by very

close contact with people who are sick or with their bodily secretions,

such as blood, urine, and feces,” said Griffin. “It isn’t spread through

the air like most other viruses. It’s usually contracted by people who

are taking care of a sick person – either a health care worker in a

medical setting or by someone taking care of a sick family member at

home.”

Additionally, the infected

patient(s) will be treated in what sounds like the Fort Knox of

treatment centers. “Emory University Hospital has a specially built

isolation unit set up in collaboration with the CDC to treat patients

who are exposed to certain serious infectious diseases,” the hospital

said in a statement.

“It is physically separate from other patient areas and has unique

equipment and infrastructure that provide an extraordinarily high level

of clinical isolation. It is one of only four such facilities in the

country.”

The hospital says its staff is

well equipped to handle the incoming patients safely. “Emory University

Hospital physicians, nurses and staff are highly trained in the specific

and unique protocols and procedures necessary to treat and care for

this type of patient,” the statement continued. “For this specially

trained staff, these procedures are practiced on a regular basis

throughout the year so we are fully prepared for this type of

situation.”

Why Isn’t There an Ebola Vaccine?

According to a Newsweek piece

published on Friday, Brantley, the American doctor who was infected with

Ebola while treating patients in Liberia, received a blood transfusion this

week from a 14-year-old boy who recovered from the disease. Though this

procedure has been around for 20 years, its effectiveness against Ebola

remains largely unknown.

"This treatment has worked in

cases of other hemorrhagic fevers similar to Ebola, because the blood is

likely to have antibodies against virus," said Griffin. "There is good

data for other similar illnesses that shows you can treat people in this

way and improve their chances of recovery. I don’t know of any evidence

that it has worked for Ebola, but I’m sure they were pretty desperate,

so it’s certainly worth trying."

The National Institutes of Health announced on Thursday

that it will be begin human tests for an Ebola vaccine. Both the size

and the high-profile nature of the current outbreak have many people

wondering why it has taken this long. The main reasons, according to

Griffin, are that outbreaks are pretty infrequent and there hasn’t been

enough pressure globally to pursue a vaccine. “Even though the past

outbreaks in Africa have been tragic, they were quickly contained and

large numbers of people have not been at risk, she said. “Developing

vaccines is a very expensive process, and there just hasn’t been the

driving forces needed to move it beyond the animal testing phase.”

There are several experimental

vaccines that have been developed that work in animals, and a few of

them have been shown to work in monkeys, said Griffin. “It’s a tricky

situation,” she continued. “There is great reluctance to use an

experimental vaccine even in desperate times. Not all vaccines are safe,

and if it turns out the experimental vaccine does more harm than good,

it would be a public health disaster.”

No comments:

Post a Comment